|

The Channeled Scabland (Sidebar 2)

The Channeled Scabland provides Creationists with a powerful example of the erosive effects of catastrophic flooding. Geologists of the early twentieth century were convinced that the slow, gradual erosion of glacier streams during an Ice Age had formed the deep scabland trenches of eastern Washington. However, one geologist of that time, J. Harlen Bretz, published papers with his conviction that the Channeled Scabland area had been formed catastrophically by the drainage of an ancient lake. From 1923 until 1969, Bretz documented more and more evidences for water erosion in the scabland. "Bretz noted dry waterfalls, high elevations of erosion in canyons, and gravel deposits of extraordinary size and often surprising locations" (Austin, et al., 1997). Finally, in the 1960's other geologists began to examine Bretz's evidence more objectively. They were quickly convinced that he was correct—there was strong evidence for an ancient lake in Montana (near the city of Missoula) and evidence for the formation of the Channeled Scabland by catastrophic flooding (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Area devastated by the Lake Missoula Flood. This prehistoric glacier ice dam in northern Idaho was breached, allowing Lake Missoula in Montana to catastrophically flood Washington State with up to 500 cubic miles of water (half the present volume of Lake Michigan), eroding the Channeled Scabland of eastern Washington. Fifty cubic miles of sediment and bedrock were eroded, forming the elaborate network of channels.

Description of Lake Missoula:

The ancient lake responsible for the erosion of the scabland has been designated Lake Missoula. According to Austin et al. Lake Missoula appears to have been a post-Flood glacial lake in Montana that was blocked by a glacier dam (up to 2,500 feet deep) in northern Idaho. The shoreline markings are at 4,200 feet above sea level, and the lake has been estimated to have had a volume of 500 cubic miles of water, covering 3,000 square miles of northwestern Montana (Austin, et al., 1997).

Description of the Channeled Scabland:

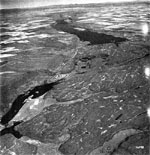

Failure of the glacial dam in northern Idaho released the waters of the enormous Lake Missoula, which rushed over the state of Washington toward the Colombia River. As the water surged, it carried chunks of ice; the ice and water carved out trenches in the basalt rock. The largest of the trenches, called Grand Coulee, is 50 miles long, two miles wide, and up to 900 feet deep (see Figure 2). Because the head of the Grand Coulee is five hundred feet above the Colombia River (to the north), it is difficult to imagine that some uniformitarian geologists had interpreted the Grand Coulee as being cut slowly and gradually by streams or even by the Colombia River.

Grand Coulee in Washington State. Figure 2. The severely eroded landscape is viewed toward the northeast, in this high-altitude, oblique, aerial photo. Water from the ice-blocked channel of the Columbia River was diverted southwestward, as a flood through the Upper Grand Coulee. The flood eroded the trench now occupied by Bank Lake (the two-mile-wide lake in top center of photo). The flood proceeded southwest, forming the severely scoured landscape of the Lower Grand Coulee (lower half of photo). The western edge of the flood-scoured zone is the 1000-foot-high cliff on the west side of Park Lake (lower left corner of photo). The boundary between the upper and lower Coulee is Dry Falls—a broad vertical escarpment (center of photo) up to 350 feet high and five times the width of Niagara Falls. Water from this flood was estimated to have had a depth of over 200 feet, and velocity of over 60 feet per second. Imagine how puny Niagara Falls would appear next to Dry Falls in its prime! (Photo copyright by Leonard Delano.)

Enlarged view of Figure 2. (111 K in size).Other interesting features of the Channeled Scabland that are evidence for great water flow are the dry waterfalls. The largest, called Dry Falls, is 300 feet high and nearly fifteen miles wide (five times wider than Niagara Falls). It has been estimated that the floodwaters that formed Dry Falls were 300 feet deep as they cascaded down.

More evidence for catastrophic flooding is in the deposition of sediments. "...(M)ore than fifty cubic miles of sediment, soil, and solid-rock basalt flows were carved out to make the elaborate network of scabland channels" (Austin, et al., 1997). Flooding of the Grand Coulee deposited thick layers of sand, silt, gravel, and boulders downstream. The presence and size of the boulders indicate that the water flow was great because it plucked large pieces of rock and transported them. The best evidence seems to indicate that Lake Missoula drained over a course of two days (Austin, et al., 1997). That means that the deep canyons and unusual trenches of the Channeled Scabland were formed in days by flooding that is unparalleled in modern times. Water has tremendous erosive abilities by cavitation, hydraulic plucking, and hydraulic vortexes (see Figure 3). The Channeled Scabland in eastern Washington is a testimony to the dynamic erosive effects of catastrophic flooding.

Figure 3.

Major agents of erosion of solid bedrock during a large flood. High-velocity flow produces cavitation downcurrent from an obstruction, as vacuum bubbles implode, inflicting hammerlike blows on the bedrock surface. Streaming flow impacts bedrock surface, causing hydraulic plucking, especially along joint surfaces. Hydraulic vortex action causes a "kolk," which exerts intense lifting force, removing blocks of bedrock.

Summary:

"The Channeled Scabland is a 16,000-square-mile area of eastern Washington, containing a variety of landforms eroded and deposited by catastrophic drainage of ancient Lake Missoula, in Montana. More than 50 cubic miles of soft silt, sediment, and solid-rock lava flows were carved out to make a vast and elaborate network of scabland channels. The abandoned, usually dry, erosional channels are called coulees. The largest erosional feature of the Channeled Scabland is Grand Coulee, a trench 50 miles long, two miles wide, and up to 900 feet deep" (Austin, 1994).

References:

Austin, S.A., 1994. Grand Canyon: Monument to Catastrophe Institute for Creation Research, Santee. p.242.

Austin, S.A.; Lumsden, R.; Morris, J.D.; Vardiman, L. 1997. "Catastrophic Geologic Change by the Lake Missoula Flood" in Mt. St. Helens Field Study Tour. Institute for Creation Research, Santee. p. 61-67.

|